History and Development

Britain’s Airborne Forces were officially formed on June 22, 1940, when Prime Minister Churchill wrote a memorandum calling for the creation of parachute and glider units. These new Airborne units were originally similar to the Commandos, tasked with conducting raids in occupied Europe for sabotage, intelligence-gathering, and demoralizing the enemy. As time went on, the Airborne Forces grew, and their role changed from raiding to capturing and holding key objectives ahead of conventional forces. The 1st and 6th Airborne Divisions spearheaded the invasions of Sicily and Normandy, in July 1943 and June 1944, respectively. The advancements in Airborne capabilities in the four years from creation to D-Day were extraordinary. One of the most important developments was that of providing supplies to the Airborne troops.

C.L.E. containers and wicker panniers on display at the Memorial Pegasus in Benouville, Normandy. Author’s photograph.

In early June 1940, the Royal Air Force established the Central Landing School at R.A.F. Ringway in Manchester. The School was created to train pilots and aircrew in emergency parachuting for escaping crippled aircraft. After the Prime Minister issued his memorandum in late June, the School found itself tasked with training soldiers in parachuting, and a handful of Army personnel were assigned to Ringway to assist the R.A.F. both with training and administration.

By September 1940, the School was renamed the Central Landing Establishment, or C.L.E. Eventually, the C.L.E. consisted of three units: the Parachute School, the Glider Training Squadron, and the Development Unit. This last unit was given the task of designing specialized equipment to support the new Airborne Forces, with an emphasis on the delivery of supplies.

In those early days, there was little enthusiasm for the Airborne Forces in either Army or R.A.F. senior command. After all, Hitler threatened to invade Britain, and the military was more concerned with preparing for a known threat than developing a new and experimental form of warfare. However, the Prime Minister insisted, and the R.A.F., quite reluctantly, transferred a handful of Armstrong Whitworth Whitley bombers to Ringway for parachute and glider training.

The Whitley was chosen as it was becoming obsolete as a front-line bomber because of its limited range and payload. It was not much better suited for dropping paratroopers. There was room for ten men to sit rather uncomfortably on the floor of the fuselage; if they were lucky, a few mattresses were provided to provide padding and insulation. The bomb-bay doors were replaced with a simple hatchway, and the men took turns dropping through the hole.

In those early, experimental days of 1940 and 1941, very little equipment was carried by the paratroopers while jumping; some method, therefore, had to be found for delivering their weapons and ammunition. The C.L.E.’s Development Unit conducted numerous experiments with air-dropped kit bags and weapon valises, large reinforced canvas bags, and wicker panniers.

Some early British Airborne equipment was based on German items; this was true for the helmet and the first “step-in” parachutist’s smock or “jumping jacket”. Additionally, the German Airborne used bomb-shaped supply containers which were air-dropped via parachute; the C.L.E. determined to develop a similar “bombcell container” for British use.

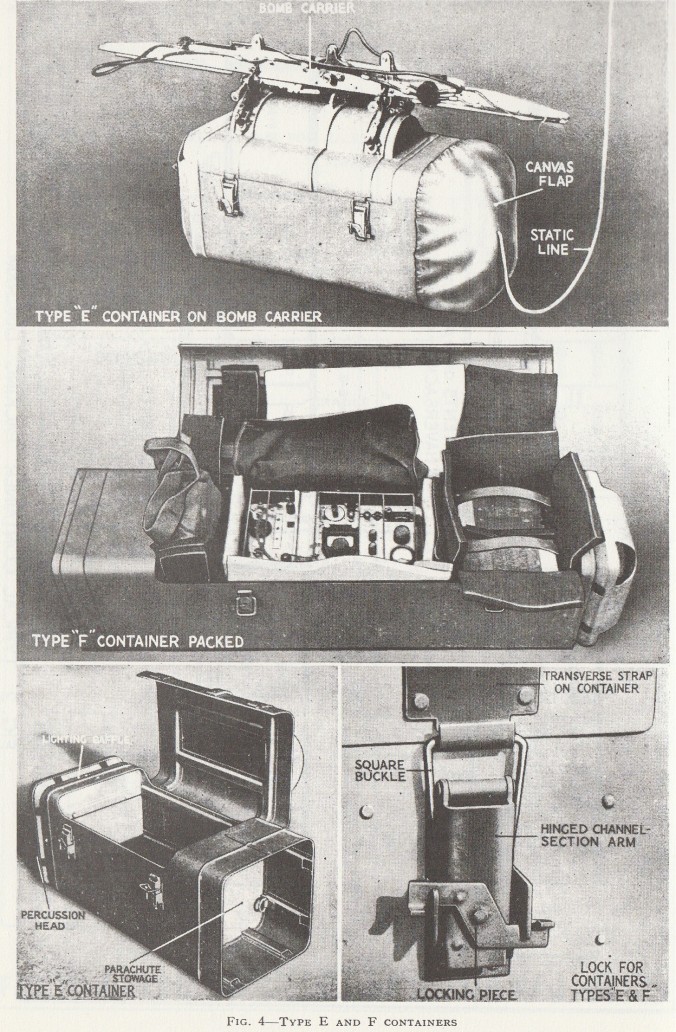

The result was the C.L.E. Container Mark I, which was a hinged tube long enough to hold rifles and light machine guns; it was made from plywood with a metal framework. One end had a fitting for a parachute, and the other end had a “percussion head” or “crash dome” attached. The percussion head was a primitive shock absorber; it was designed to collapse upon impact, thereby reducing the amount of force imparted on the container’s contents. The percussion head was detachable and easily replaced, so that the rest of the container could be reused. A battery-powered beacon could be attached to the container to make it easier to find in the dark. By early 1943, the Mark I was joined by the Mark I.T., which was similar in size and appearance, but made entirely of sheet metal. There was also the Mark III, which had the same diameter, but was eight inches shorter. Additionally, the Type E and Type F Containers were adopted; these were rectangular in shape, and designed specifically for radio equipment.

In April 1944, the 1st and 6th Airborne Divisions took part in a large-scale exercise in preparation for the invasion of occupied Europe. In this photograph, two paratroopers attach a C.L.E. container to the hardpoint of a Douglas Dakota. Note that the static line has already been attached, and the cradle is being fitted to the hardpoint. This appears to be a Mark I container. Photo from the Imperial War Museum (H 37727).

The containers could be attached to hardpoints on the exterior of an airplane’s fuselage; each hardpoint had a mechanical release operated by the pilot. The Type E and F containers had attachment points built into the lid, but the cylindrical containers had to be fitted with a cradle which was then attached to the hardpoint. Additionally, the cylindrical containers could be carried and dropped from the bomb rack of a standard bomber, which had the advantage that no additional training or aircraft modifications were required. Typically, the containers were fitted with static line parachutes, although some applications required a drogue parachute to deploy the main canopy.

In February 1942, the C.L.E.’s Development Unit was renamed the Airborne Forces Experimental Establishment. Later that year, the R.A.F. first started using the Douglas Dakota (the Lend-Lease version of the American C-47); it was the best cargo and transport aircraft of the war. For dropping paratroopers, the Dakota was modified by adding seats and a static line, and the soldiers jumped from a side door, which was considered by the troops to be vastly superior to dropping through the hole of a converted bomber. These aircraft were further modified by adding six hardpoints under the fuselage for carrying containers.

As time went on, methods were developed so that paratroopers were able to drop with their weapons and other equipment, reducing their dependency on the supply containers during the initial drop. However, the Airborne Forces grew from small raiding forces to full divisions intended to take and hold vital objectives until relieved by ground forces; aerial resupply became essential for providing ammunition, rations, medical supplies, and all the other items necessary to fight and survive on the battlefield. Aerial resupply was also used extensively in the Far East, where heavily-laden trucks found it difficult to navigate the poor roads and dense jungles found in Burma.

The containers continued to be used after World War II, although they were re-named; the initials “C.L.E.” were retained, but the name “Container, Central Landing Establishment” was replaced with “Container, Light Equipment”. They were last used operationally in 1956, when 3rd Battalion, the Parachute Regiment, dropped into Egypt during the Suez Crisis. The Mark I and Type E containers were considered obsolete by 1960, but the other containers were still used for training purposes at least through the 1960’s.

C.L.E. Containers: Variants and Details

The C.L.E. Mark I Container was made from a metal framework faced with plywood; it was constructed as two halves that were then hinged together to form a cylinder. It was closed with two external latches. The Mark I was 6 feet 2 ½ inches in length, with a diameter of 1 foot 2 inches; it weighed 103 ½ pounds empty, with a maximum loaded weight of 350 pounds.

The C.L.E. Mark I.T. Container was the same length as the Mark I (6 feet 2 ½ inches). However, it was made entirely of metal, and took the form of a flat-bottomed cylinder. It was somewhat heavier at 135 pounds, but had the same maximum loaded weight of 350 pounds. Like the Mark I, it closed with two external latches. After World War II, the Mark I.T. was referenced as the Mk. 1 (T).

April 1944; another photograph from the same exercise as above. Soldiers maneuver C.L.E. containers from trucks to the waiting aircraft. The shape indicates these containers are Mark I.T. variants. Photo from the IWM (H 37700).

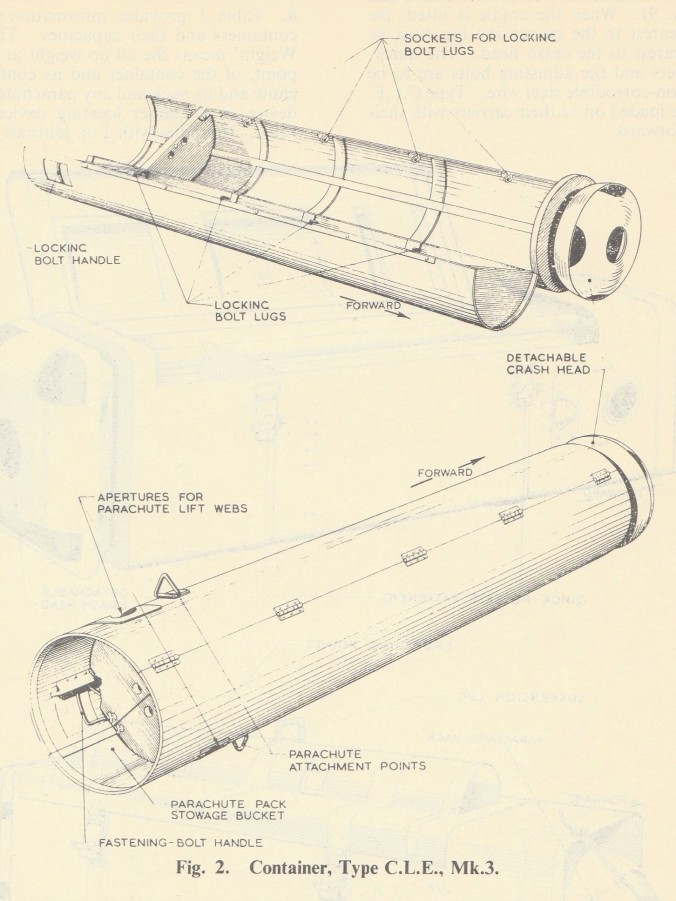

The C.L.E. Mark III Container was shorter than the Mark I at 5 feet 6 ½ inches. It was completely cylindrical, with a diameter of 1 foot 2 inches. The Mark III was made of either all-metal or metal-framed plywood construction. The Mark III weighed 113 ½ pounds empty; the original maximum loaded weight was 350 pounds, but after extensive use the maximum weight was revised to 400 pounds. Unlike the earlier containers, the Mark III had an internal locking mechanism; a rectangular cutout at the parachute end gave access to the locking handle. By 1943, the Mark III was intended to replace the earlier containers, unless a specific load required the greater length. Post-war manuals reference the Mark III as the Mk. 3.

The Type E Container was rectangular in shape with a hinged lid, and was designed specifically for dropping the Number 18 wireless/telegraphy set. While the 1943 manual does not list the size of the Type E, it does give the weight as 89 pounds empty, or 190 pounds when loaded with the No. 18 W/T set; the 1960 manual does not reference the Type E.

Type E and Type F containers; illustration from Air Publication 2453, Volume I, Section 2, January 1943.

The Type F Container was also rectangular, but longer than the Type E; it was 5 feet 8 ½ inches long, and 1 foot 2 inches tall by 1 foot 2 inches wide. The Type F could carry several different wireless/telegraphy sets, specifically the No. 11, 19, 21 or 22 sets. The container weighed 92 pounds empty; the loaded weight varied depending on the type of W/T set carried, but the maximum weight was 340 pounds.

Regardless of type, the training manuals stated that three or four men were needed to handle a loaded container*.

Other Methods

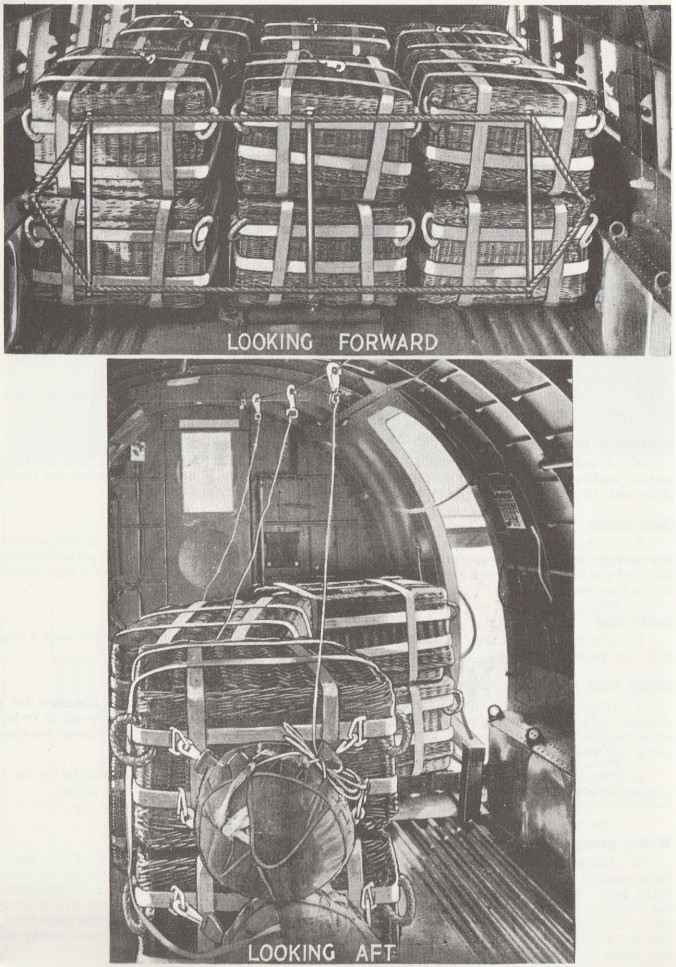

Another item developed for dropping supplies was the wicker pannier, which was essentially a very large wicker basket. There were two halves, the top being slightly larger than the bottom so it could fit over it. The two halves were not attached; there were no latches or hinges. Instead, the two halves were lashed together with webbing straps. This gave the advantage that the size of the load did not have to be precise; the pannier could be expanded as needed. The top half had four rope handles at the corners. The wicker pannier had a maximum loaded weight of 500 pounds, greater than any of the “bombcell” containers.

Typically, two panniers were bundled together; this was referred to as the “daisy chain” method, and naturally allowed for the panniers to be dispatched in half the time. One pannier was stacked on top of the other, and they were attached with lightweight ties. Each pannier had its own parachute, but with different lengths of static line; this would cause them to open at different times, breaking the ties and separating the two panniers.

Wicker panniers loaded in a Douglas Dakota; they are stacked and ready for a “daisy chain” drop. Illustration from Air Publication 2453, Volume I, Section 5, Chapter 2, January 1943.

A variant of the Dakota was designed specifically for dropping pannier loads; a series of rollers was added to the floor to make it easier to move the panniers to the door for the drop. With a pair of panniers having a combined weight of up to 1000 pounds, the rollers were necessary for the “daisy chain” method. It was this type of aircraft which was piloted by Flt. Lt. David Lord, V.C., when he was shot down over Arnhem.

Some supplies were bundled together and fitted to a cargo parachute without the use of a container; this method became increasingly common as the war progressed.

The Drop

When first adopted, the C.L.E. containers were dropped in the middle of the “stick” of paratroopers to make it easier for the soldiers to find their weapons and equipment. As time went on, there was less reliance on the containers for the initial drop, and the containers could be dropped before, after, or even simultaneously with the paratroopers. A delayed-opening device was developed for the cargo parachute which made it safer to drop the containers alongside the paratroopers.

Operation Varsity, the crossing of the Rhine, March 1945. The container in the foreground is a Mark III; the rectangular opening for the latching mechanism’s operating handle can be clearly seen. Photo from the Imperial War Museum (BU 2531).

Most resupply drops were made from about 600 feet, regardless of type of aircraft or containers used. However, for some operations, a fast-moving fighter-bomber could carry three or four bombcell containers and get through heavy anti-aircraft fire more easily than a large bomber or cargo plane; this method was primarily used for high-priority supplies or for clandestine operations, such as dropping supplies to the various Resistance organizations.

The standard cargo parachute had a 28-foot canopy, although smaller parachutes of 18 feet and 24 feet were also made. The cargo parachutes were made in a variety of colors so that supply drops could be color-coded. Different types of supplies, such as rations, ammunition, and medical equipment, could be designated by the color of parachute; another method would be to color-code the supplies intended for different units. There was not a set system, and the color-coding was varied for each operation.

Operation Market Garden, September 1944. A Type F container is recovered. Photo from the National Army Museum.

While the R.A.F. naturally provided the aircraft and pilots, loading and dispatching the containers was the responsibility of the Royal Army Service Corps. While the bombcell containers were deployed mechanically by the pilot or his designee, the wicker panniers required specially-trained Air Dispatchers to fly in the cargo hold and maneuver the panniers to the door. Other R.A.S.C. troops were assigned to the Airborne Divisions who were responsible for gathering the supplies from the drop zones and distributing them to the rest of the Division.

Reenacting Tips

Original C.L.E. containers are highly prized on the collector’s market. I have personally only seen originals in museums, and have never seen one in the United States.

My reenacting unit is very privileged to own a reproduction of the C.L.E. Mark III Container. Several years ago, a member of the unit sent me an interesting proposal: he was a professional machinist, and wanted to build a reproduction container. He offered to make the reproduction at no charge for his labor, but requested that the unit pay for materials. However, he had only seen photographs and asked if I had access to any schematics. As unit leader, I quickly approved his proposal. I had recently acquired a copy of the 1960-dated Military Parachutists Manual. Even though published well after World War II, the manual included a chapter on resupply containers, including the Mark I.T., Mark III, and Type F. The chapter contained line drawings, measurements, and weight tables; I scanned the entire chapter and sent it to my friend.

The Mark III (or Mk. 3) container as illustrated in the Military Parachutists Manual (Air Publication 4215 / War Office 9514), January 1960.

The result was a reproduction of the Mark III Container. Due to the limitations of the sheet metal available, the reproduction is slightly shorter than the original, and significantly lighter in weight. However, I am responsible to single-handedly store and transport it, so I am very grateful it is not the full weight. The crash dome is made from fiberglass and is somewhat fragile; however, the internal locking mechanism functions like the original. I am very pleased with the finished product, and it has been a tremendous asset for our living history events. We primarily use the reproduction container for public displays, particularly at air shows. We have also used it at tactical reenactments, including events based on the Oosterbeek perimeter during Operation Market Garden.

Reproduction C.L.E. Container Mark III at a public display. Author’s photograph.

*My favorite film is A Bridge Too Far; however, while the scene where the young soldier carries a loaded container over his shoulder is very dramatic, it is also highly unrealistic.

Sources

By Air to Battle: The Official Account of the British First and Sixth Airborne Divisions

His Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1945

Military Parachutists Manual

Air Publication 4215, War Office Code 9514

Section 6, Chapter 3: “Supplies Dropping Containers”

January 1960

Bouchery, Jean, and Charbonnier, Phillipe

D-Day Paratroopers: The British, The Canadians, The French

Histoire & Collections, 2004

Gregory, Barry

British Airborne Troops

MacDonald & Jane’s, 1974

Tanner, John, General Editor

RAF Airborne Forces Manual: The Official Air Publications for RAF Paratroop Aircraft and Gliders, 1942-1946

RAF Museum Series, Volume 8

Arms and Armour Press, 1979

[Includes Reprints of Air Publications 2453 (January 1943) and 2453A (July 1945)]

The website of the Airborne Assault Museum

www.paradata.org.uk