It has become my personal tradition, since starting this website, of writing about the Battle of Arnhem every September. This year, I decided to write a review of The Memory Endures: The Story of a Grenadier Guardsman and Pioneer of the Parachute Regiment, 1937 – 1945, by Reg Curtis (1920 – 2016). This is the autobiography of one of the original members of the British Airborne Forces who fought throughout the war, including the Battle of Arnhem.

Reg Curtis was born in South East London into a family with a strong military tradition; his father and uncle were Army veterans. Young Reg wanted to join London’s Metropolitan Police, but believed a term of service in the Army, particularly the Guards, would greatly improve his chances; he enlisted in 1937.

The Guards have always preferred tall recruits; at 6 feet, 2 inches, Curtis easily met their standard. Curtis underwent training at the Guards Depot and was posted to the 3rd Battalion, The Grenadier Guards. He participated in numerous ceremonial functions; the Guards’ emphasis on drill and a polished appearance instilled Curtis with a strong sense of self-discipline.

When war with Germany was declared in September, 1939, Curtis’ battalion was sent to France as part of the British Expeditionary Force. During the winter, they patrolled the area between the Maginot Line and the Siegfried Line; while they avoided contact with the Germans, they performed reconnaissance and reported on enemy activity.

The Germans launched their onslaught of France and the Low Countries in May, 1940. The 3rd Grenadier Guards defended as best they could, but suffered heavy casualties from enemy artillery and aerial bombing; the survivors were ordered to make their way to Dunkirk. During the long retreat, Curtis saw a number French civilians who had been killed or injured; whenever possible, he stopped to bandage the wounded before moving on.

Curtis spent five days at Dunkirk waiting for his turn to board ship for England. During that period, he and others were sent out to bury the dead, assist the wounded, and search for rations and ammunition. He was finally assigned to a minesweeper; exhausted, he slept for the entire journey back to England.

Only about 50 men from 3rd Battalion made it back from France. Curtis was made Lance Corporal and sent on a section leader’s course. He was granted leave upon receiving news that his parents’ London home had been destroyed by German bombing; fortunately, his family had been in a bomb shelter and survived.

One morning on parade, an announcement was made that a “new kind of soldier” was wanted for training in parachuting. Curtis thought about the civilian losses in France and the bombing raids at home; he volunteered and was accepted. Prior to leaving his battalion, he was interviewed by the commanding officer who told him to remember the traditions and high standards of the Guards.

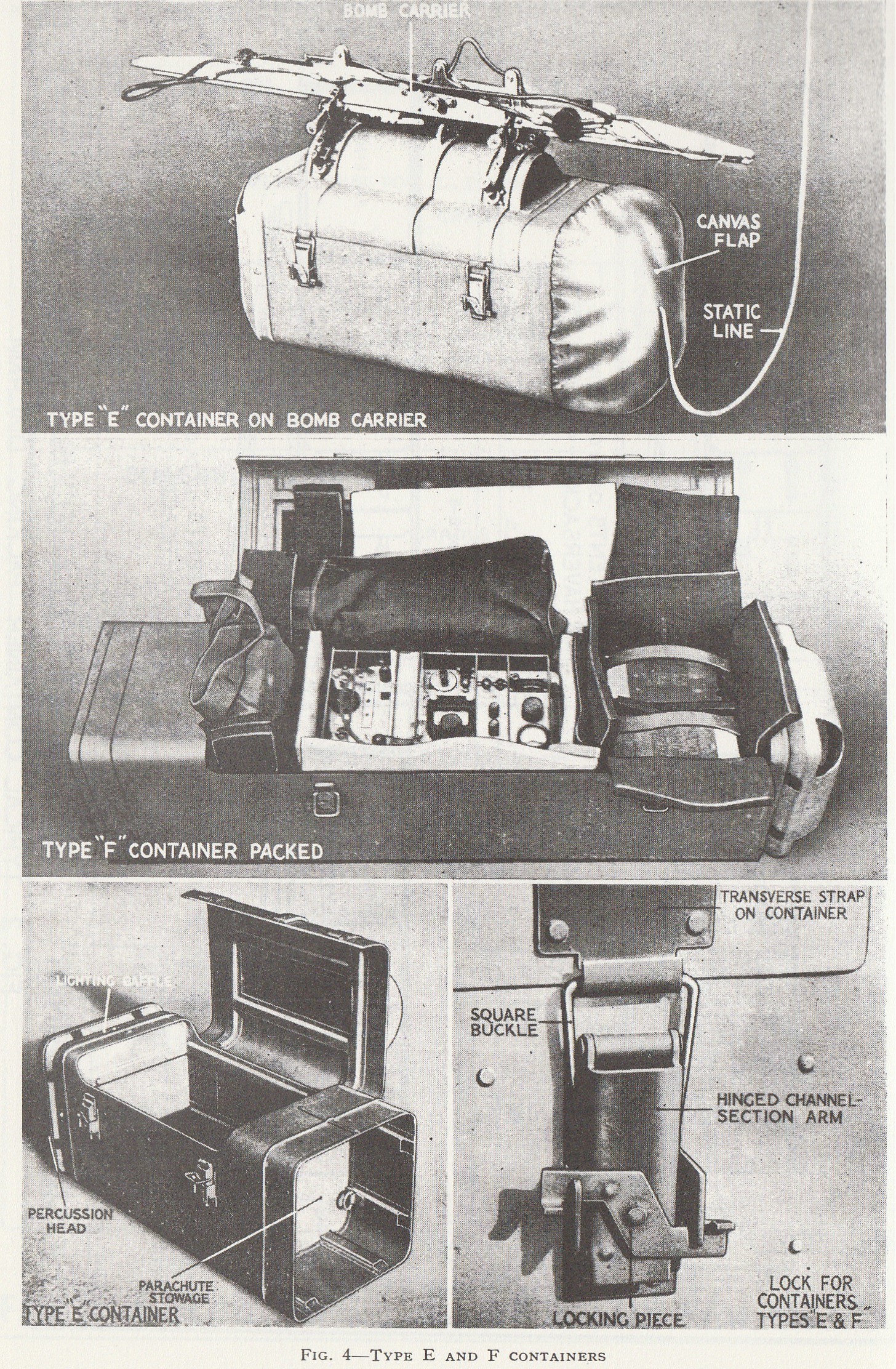

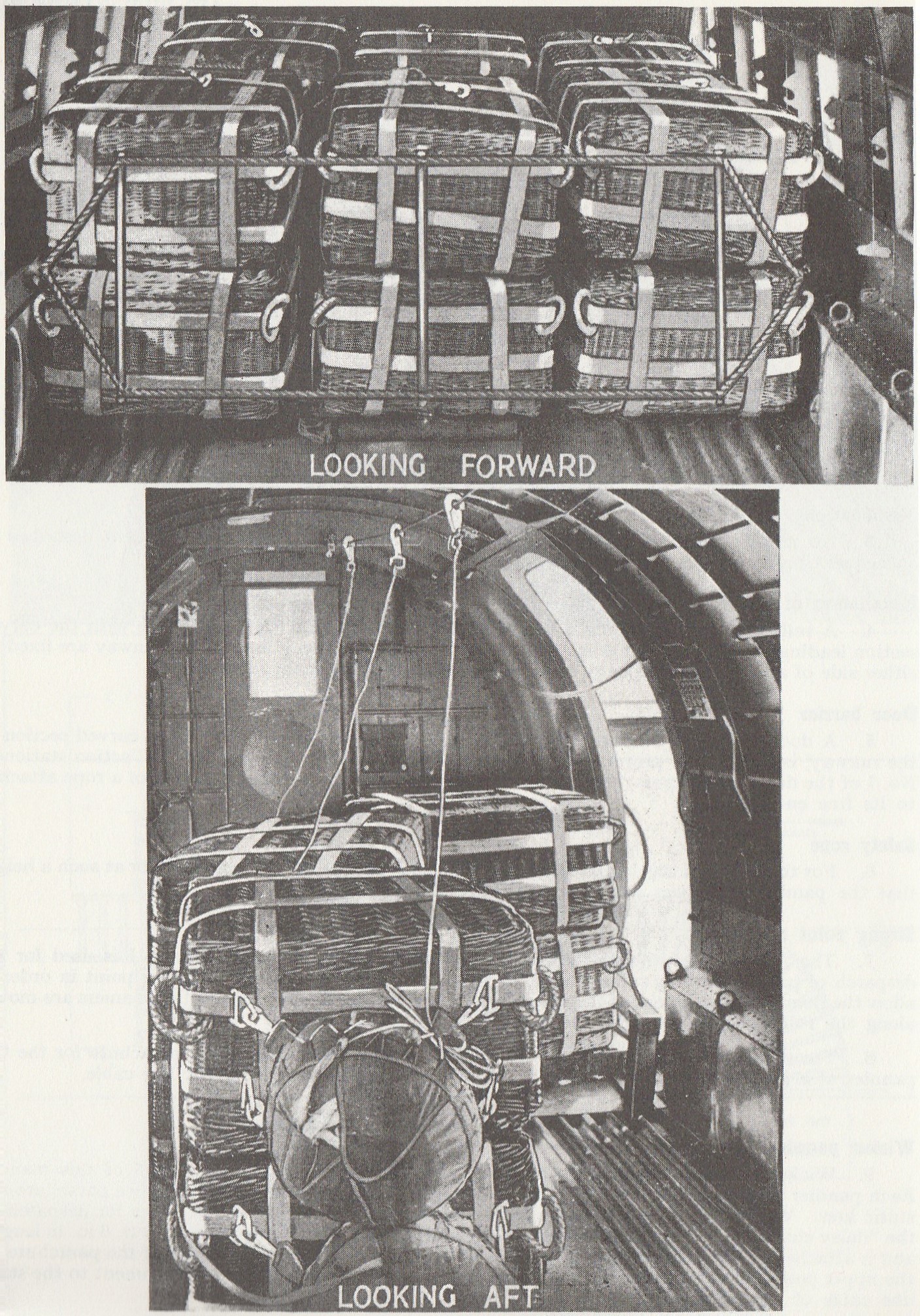

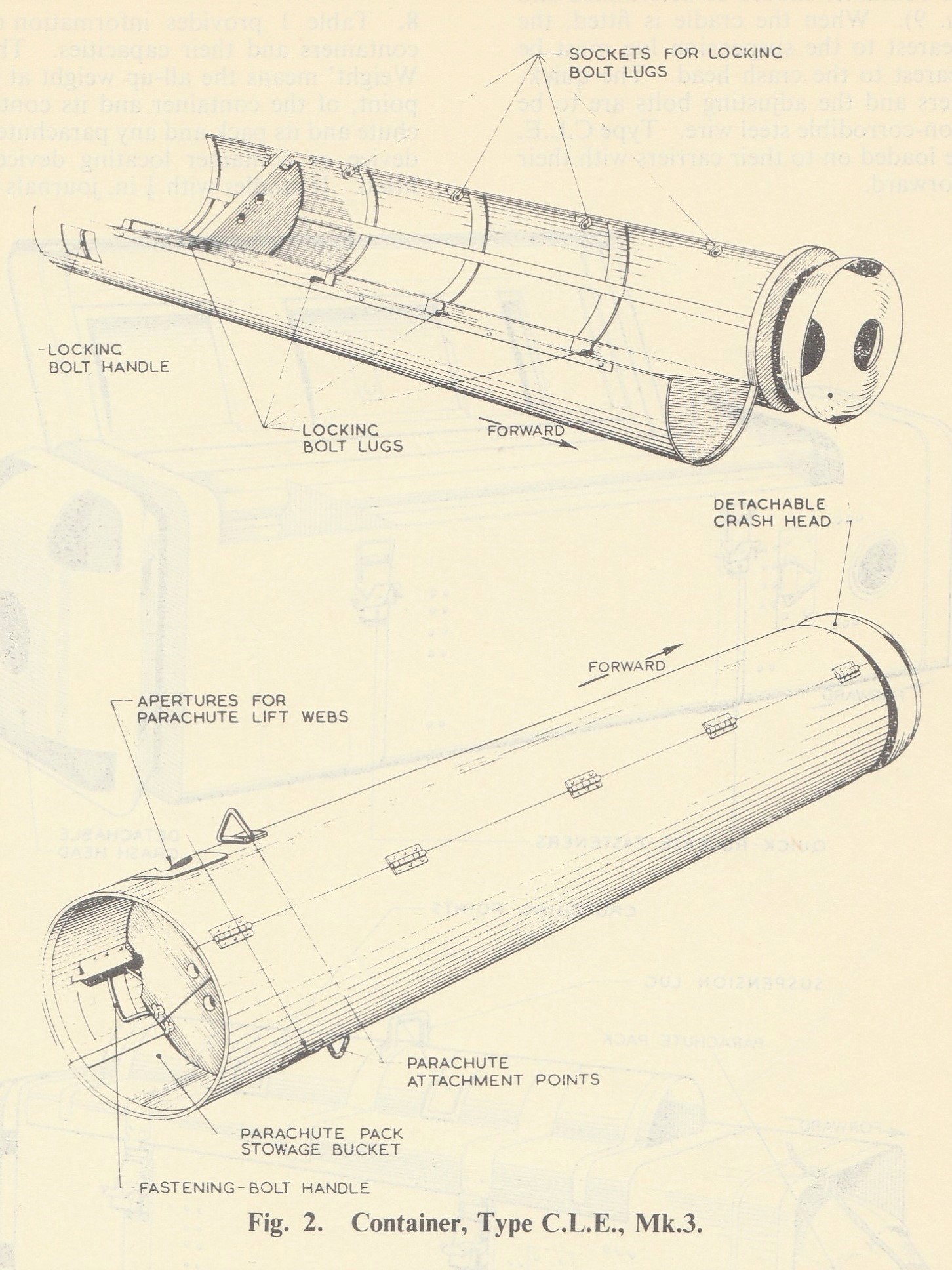

Curtis joined L Troop, No. 2 Commando, which had been selected for parachute training. British military parachuting was in its infancy; techniques and equipment were still being developed and perfected. There were a number of injuries and even deaths during those early days, and the volunteers must have been extraordinarily brave. One training apparatus in particular was abandoned as it caused more injuries than actual jumps had. The only available airplane was the obsolete Whitley bomber; on his first jump, Curtis bloodied his nose dropping through the hole in the fuselage floor, an injury so common that it earned its own name, “ringing the bell”. Curtis was injured again during a demonstration drop put on for the press, which should have been canceled because of bad weather. The strong winds caused Curtis’ parachute to oscillate; he had a hard landing which knocked him unconscious and put him in the hospital for a week.

Curtis also underwent survival training in the Scottish Highlands in the harsh winter, living off the land, having to hunt game to supplement the meager tinned rations provided. Other training involved long marches and runs, as well as nighttime navigation. On some exercises, No. 2 Commando took on the role of enemy parachutists; the commandos learned valuable lessons in unconventional warfare but also gave regular units and the Home Guard experience in responding to an invasion.

Curtis described his comrades as “Para-Commandos”, reflecting the original role of the Airborne as raiding forces. For his height, Curtis was given the nickname “Lofty”. Eventually, No. 2 Commando was renamed the 11th Special Air Service Battalion, then renamed again as 1st Parachute Battalion in 1941. Two additional battalions were created; together, they formed the 1st Parachute Brigade. Curtis was part of the Airborne Forces during the establishment of the Parachute Regiment and the adoption of the maroon beret and Pegasus insignia. While the men came from all across the Army, they developed their own Esprit de Corps; jump-trained engineers, signalers and medics joined the Brigade and earned the respect of the parachute infantry.

In November, 1942, 1st Parachute Brigade was shipped to North Africa to support 1st Army and the Operation Torch landings. They landed in Algiers and established themselves at an airfield near Maison Blanche. Each of the three battalions performed its own operation; 1st Battalion captured the enemy airstrip at Souk-el-Arba, Tunisia, then moved on to Beja and Medjez-el-Bab, where they spent several weeks patrolling and skirmishing with the enemy. The Brigade spent several months in Tunisia fighting as standard infantry, typically wherever the fighting was heaviest. At Djebel Mansour, Curtis fought until he ran out of ammunition; he then helped a wounded comrade across the difficult terrain to an aid post. The Brigade suffered a number of casualties in Tunisia, but inflicted far greater losses on the enemy.

Once victory in North Africa had been achieved, it was time for the next objective: Sicily. The Allies launched their invasion in July, 1943. After the beachhead was secured, 1st Parachute Brigade dropped onto the island to capture the Primosole Bridge near the Catania Plain. The nighttime drop was badly scattered; Curtis, like many others, found himself miles from the objective and had to make his way in the dark towards the bridge. The paratroopers were able to capture their objective, but after expending nearly all of their ammunition, they were driven from the bridge. Eventually, the ground forces of 8th Army linked up with the Brigade and recaptured the bridge. Once again, the paratroopers had fought hard against a strong enemy, but paid a terrible price.

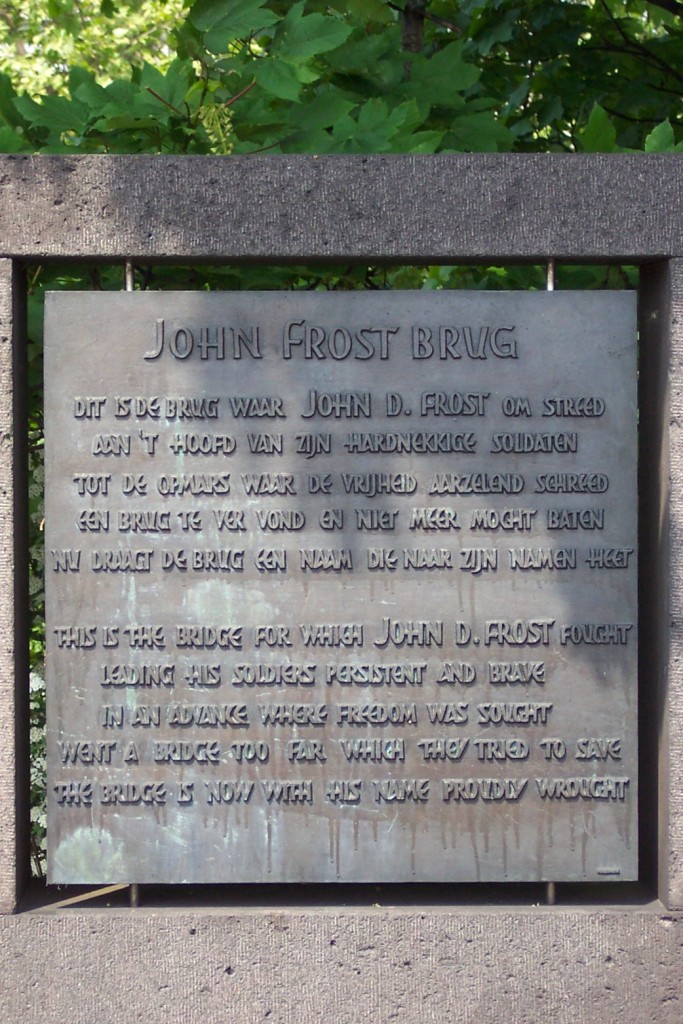

After Sicily, the Brigade returned to Britain to recruit and train replacement troops. 1st Airborne Division prepared for numerous operations in the summer of 1944, while 6th Airborne was fighting in Normandy. They finally had their chance in September, with Operation Market Garden. The operation started well enough, with good weather and little resistance at the drop zones. While 2nd Parachute Battalion was to capture Arnhem bridge, 1st Battalion was directed to form a defensive line along the town’s northern border.

1st Parachute Battalion never reached its destination. The Germans reacted quickly to the British drop and formed blocking lines along likely approaches; it was not long before 1st Battalion came under heavy fire. The Battalion attempted to break contact with the enemy by heading south, then pushing forward again towards Arnhem. They reached the outskirts of the town and took cover in the buildings, but found themselves up against tanks, self-propelled guns, and dug-in machine guns.

During the confused fighting, Curtis was badly wounded; a bullet hit him just above the knee and shattered his right leg. Curtis was placed on a jeep and evacuated to the dressing station at the Hotel Tafelberg in Oosterbeek. He spent several uncomfortable days at the Tafelberg; the medical staff did all they could, but as the battle progressed, the front line moved uncomfortably close to the dressing station. Eventually, the Tafelberg was overrun; the medical staff and hundreds of wounded, including Curtis, became prisoners.

For the next two months, Curtis was moved from one hospital to another. Attempts to set his shattered leg failed, and the decision was finally made to amputate. Fortunately, after the operation Curtis’ overall health improved greatly. Curtis was taken to a series of prisoner of war camps, until finally liberated by American forces in April 1945.

I have read a number of personal accounts by veterans of the 1st Airborne Division; The Memory Endures is the only one I have read by a member of 1st Parachute Battalion. The firsthand experiences of several difficult operations makes for fascinating reading; Curtis was one of only a handful who fought in North Africa, Sicily and Arnhem. However, I found the descriptions of the early days of the British Airborne Forces particularly interesting; not just the development of parachuting techniques and equipment, but also the men’s training in unconventional warfare.

It is one thing to read the War Diaries and other official histories; it is quite another to read about the same events in the language of the individual soldier. In Tunisia, 1st Parachute Brigade spent several weeks in Tamera, but to the troops, it was ironically called “Happy Valley”, with the high ground termed “Shell-Shock Ridge”. Nearby hills were known as “Bowler Hat” and “The Pimple”. In Curtis’ memoirs, he used a unique spelling of the Arabic call that became the paratroopers’ battle cry; to Curtis, it was “Who-oooh Mohamad!”

Throughout the book, the language is direct and rather conversational in tone, but becomes much more vivid when describing combat. Curtis describes the sensations of battle: the sights, sounds, even smells, as well as his emotional responses to such experiences.

Reg Curtis wrote The Memory Endures in 2014, two years before he died at the age of 96. This is an extraordinary personal story, and I highly recommend it.

The Memory Endures: The Story of a Grenadier Guardsman and Pioneer of the Parachute Regiment, 1937 – 1945 is only available through Pilots Publishing. All profits are donated to Support Our Paras, the charity specifically dedicated to supporting Airborne veterans.

Pilots Publishing: The Memory Endures